It should come as no surprise that navigating the Grand Canyon is a serious undertaking even in today’s GPS age. So before I embarked on a self-support kayak trip down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, I made sure I was prepared with the most up to date, accurate navigational data and tools.

It should come as no surprise that navigating the Grand Canyon is a serious undertaking even in today’s GPS age. So before I embarked on a self-support kayak trip down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, I made sure I was prepared with the most up to date, accurate navigational data and tools.

My primary navigational aid was the excellent waterproof Guide to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon by RiverMaps that includes a mile-by-mile breakdown of the entire navigable river with excellent topographic maps and descriptions of all major rapids, all campsites, and points of interest. I carried the guidebook under bungee straps on the bow of my Rogue 10 kayak which allowed me act as my own guide throughout the 280 mile trip.

Prior to the trip when I was perusing the RiverMaps website, I discovered that the authors also provide a full downloadable set of waypoints that correspond to every single rapid, campsite, and point of interest that is described in the guidebook. Being the GPS nerd that I am, I was beyond excited as I downloaded the file.

But then I realized that I needed a method to compare my current GPS location to the set waypoints from the paper map. Previously, the only way I knew to do this was to load the waypoints onto a handheld GPS and then visually compare my current location with the preloaded waypoints on the map page of the GPS. Although this method could work fine in many circumstances, I knew it would be beyond inconvenient to try to simultaneously operate a handheld GPS and kayak the huge rapids of the Grand Canyon.

After a few hours of internet research and playing around, I came up with a unique method that kept me constantly and unobtrusively up to date on my position in the canyon and that to my knowledge has never been documented and shared on the internet for others to benefit from. What I wound up doing was creating proximity alerts of all the Grand Canyon waypoints on my wrist-worn Garmin Fenix GPS. If you’re interested in learning more about this, keep reading below!

I carried two GPS units on the Grand Canyon that complemented each other very nicely—the wrist-worn Garmin Fenix and the hand-held Garmin Oregon 600t. I should begin by saying that with these units (and most other recent GPS units), it is a trivial matter to add new waypoints to the unit. You simply connect the GPS to your computer with its USB cable and then drag-n-drop the GPX waypoints file from your computer to the G:\Garmin\GPX folder on the GPS.

With that step complete, all of the waypoints will appear on the unit’s map and will be available for navigation on the unit. But for my purposes, I didn’t want to continually look at the map nor did I want to navigate from point to point. What I wanted was the same behavior that my automotive GPS exhibits when it gets near school zones and speed traps—I wanted the GPS to keep track of my location relative to the waypoints and then notify me when I neared them. In other words, what I wanted were proximity alerts for my Grand Canyon waypoints.

Proximity Alerts: Waypoints or POIs?

After I learned that the correct term for this functionality is proximity alerts and that Garmin supports them, I was presented with another learning moment—did I want to implement them as part of a waypoint file or as part of point of interest (POI) file? As it turns out, I probably could have used either technique successfully, but I chose to implement the proximity alerts using traditional waypoints since I could manually manage them directly on my GPS units in the field without the need for a computer. Here is a summary of the pros and cons of each technique:

After I learned that the correct term for this functionality is proximity alerts and that Garmin supports them, I was presented with another learning moment—did I want to implement them as part of a waypoint file or as part of point of interest (POI) file? As it turns out, I probably could have used either technique successfully, but I chose to implement the proximity alerts using traditional waypoints since I could manually manage them directly on my GPS units in the field without the need for a computer. Here is a summary of the pros and cons of each technique:

POI File

- Binary file that contains all of the waypoints

- Smaller file size than waypoint file since it is in binary format

- Can only be edited with the aid of a computer with tools like Garmin BaseCamp and Garmin POI Loader

- Provides neatly packaged set of waypoints that cannot be easily edited by most users (i.e., provides a level of security/stability to the file contents)

Waypoint File

- ASCII (human readable) text file that contains all of the waypoints

- Larger file size than POI file since it is in ASCII file format

- Can be created or edited on a computer using Garmin BaseCamp or any text editor

- Individual waypoints can be edited and/or deleted directly on the GPS unit without the aid of a computer

Given the complete isolation of our expedition, I wanted to retain the capability of editing the proximity alerts for the waypoints in case I wanted them configured differently after using them for a while on the river. As it turned out, I didn’t edit any of the waypoints during the trip, but I was able to delete them throughout the trip in order to speed up performance of the Fenix GPS that operated slowly with all that data on board. For those reasons, I decided to implement the proximity alerts in a waypoint file.

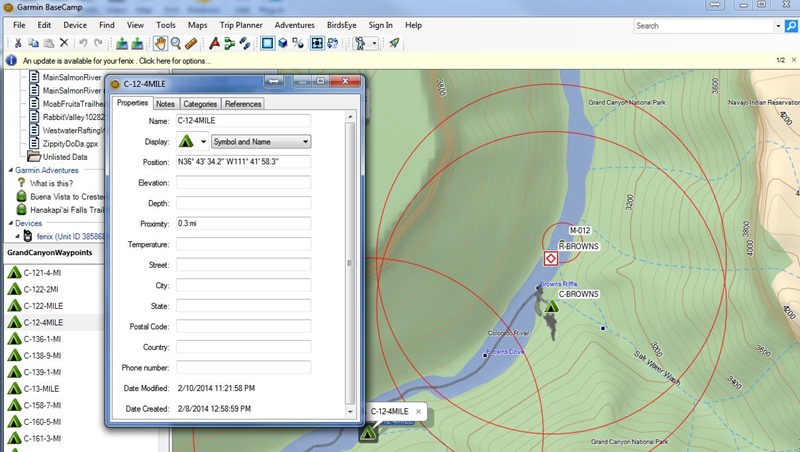

Creating Proximity Alerts in BaseCamp

It turns out that creating proximity alerts is a piece of cake if you use Garmin BaseCamp software on your computer. Begin by importing all of your trip’s waypoints into BaseCamp (in my case, the waypoints I downloaded from RiverMaps in GPX file format). Next, select a single waypoint or multiple waypoints and bring up the Properties for those waypoints. Among other properties such as Name, Symbol, Position, and Elevation, you’ll see the Proximity field. Simply enter the radius at which you want to be alerted by the GPS when approaching or leaving the waypoint in appropriate units of feet, meters, miles, or kilometers.

In my case, I wanted to be alerted with different levels of preparedness depending on the type of waypoint. For instance, I set the mile marker distance to be about as wide as the average river width so that I’d be sure to pass through the waypoint proximity zone as shown for M-012 in the screen snap above. In the case of camps and POIs (generic term unrelated to POI files from above), I wanted to be alerted with enough forewarning that I’d be able to get to the correct side of the river to get out. And for rapids (some of which are huge and very consequential), I wanted plenty of forewarning so we could regroup and possibly get out to scout the rapid. The distances I used for proximity radii for the different waypoint types were:

- Mile markers: 150 feet

- Camps: 600 feet

- Points of interest: 600 feet

- Rapids: 1/4 mile

After the proximity alerts were set for all the waypoints, I then exported all of the modified waypoints to a new GPX file (that you can download here) and copied it to my Garmin Fenix and Oregon 600t.

Once the GPX waypoints file was copied to the GPS units, there was one final step to use the proximity alerts. In the Fenix, there is a setting for Proximity under the Alerts menu that allows them to be turned on/off, edited, and for the notification type to be set. In the Oregon, the setting was buried under the Tones Setup item. In my case, I set the Fenix to alert me with both a tone and a vibration and then turned on the alerts.

My Experience Using Proximity Alerts in the Grand Canyon

So with all of my research and preparation, how well did proximity alerts actually perform during my self-support kayak trip down the Grand Canyon?

First off, I should mention how I used my two GPS units. Most of the time, the Oregon sat safely stowed in a Watershed bag on my lap and was only retrieved at times of confusion regarding our campsite. As such, I don’t have a great deal of feedback regarding its usefulness other than to say that it did help us locate our camp on two occasions. As I mentioned earlier, my primary means of navigation was using the RiverMaps guidebook on my kayak deck while wearing the Garmin Fenix on my wrist.

Each day, I started a new activity on the Fenix that recorded our progress down the canyon including scouting of rapids and side hikes. I set the activities to record to .FIT files, since they result in much smaller file sizes than GPX files, and I didn’t want to run out of space during our 12 day, 280 mile trip. After the trip was complete, I assembled all of the day’s tracks and camp waypoints into a single GPX file (using the technique I developed here) that you can download here.

Each day, I started a new activity on the Fenix that recorded our progress down the canyon including scouting of rapids and side hikes. I set the activities to record to .FIT files, since they result in much smaller file sizes than GPX files, and I didn’t want to run out of space during our 12 day, 280 mile trip. After the trip was complete, I assembled all of the day’s tracks and camp waypoints into a single GPX file (using the technique I developed here) that you can download here.

In the past, I would have used each day’s GPS-computed distance to figure out where we were at any given point in time relative to our starting position. For example, if we camped at Mile 17.7 and my GPS indicated that we’d traveled 6.3 miles, I would safely assume that we were at Mile 24 and would soon be approaching Georgie Rapid. Although this approach has worked well for me in the past, the deep, tight confines of the Grand Canyon often resulted in spurious calculations by the GPS that erroneously increased the calculated distance by 20-50%. So if I had used my old method, I would have been far off from my actual position each day.

Fortunately, my new method of proximity alerts didn’t suffer from the accumulation of errors the way my old technique did. Since at any given moment, the GPS was highly accurate, the Fenix was able to accurately compare my present location to the list of waypoints and tell me precisely when I crossed the imaginary threshold that I’d set weeks earlier on my computer. At that moment, the Fenix would beep and vibrate as it displayed the name of the waypoint I just got close to. One of the other paddlers, Peter, also wore a Fenix with the same proximity waypoints, and as a testament to their accuracy, we would hear them each beep as we passed over the same imaginary lines on the river.

As an example of how effective the proximity alerts were at notifying me, early in the trip we entered one of our first rapids with big, rowdy waves and my entire attention was focused on paddling the big whitewater and avoiding tipping over my heavy kayak that was loaded with two weeks of supplies. Just as a big wave crashed over my bow and then my whole body, I felt a strange vibration on my left wrist. As I emerged from the wave and took my next stroke, I glanced at my wrist and was easily notified of the mile marker that I’d just passed. No other navigational technique would have been able to communicate my exact location to me under those circumstances as well as the Fenix had with proximity alerts.

As an example of how effective the proximity alerts were at notifying me, early in the trip we entered one of our first rapids with big, rowdy waves and my entire attention was focused on paddling the big whitewater and avoiding tipping over my heavy kayak that was loaded with two weeks of supplies. Just as a big wave crashed over my bow and then my whole body, I felt a strange vibration on my left wrist. As I emerged from the wave and took my next stroke, I glanced at my wrist and was easily notified of the mile marker that I’d just passed. No other navigational technique would have been able to communicate my exact location to me under those circumstances as well as the Fenix had with proximity alerts.

At this point, you should be convinced that the proximity points on the Fenix GPS were easy to add, were very accurate, and very effective at notifying me even under the most challenging of circumstances. So the only real questions that remain are: didn’t it disturb me to hear my watch constantly beeping and vibrating when I was supposed to be enjoying the wilderness, and did it actually help with navigation throughout our trip?

The answer to the first question is completely a personal opinion. I know other people who would never dare have technology spoil their experience of the great outdoors, but they are often the same people who relish the adventures that ensue when they find themselves lost. For me, the alerts were part of the overall navigational experience that allowed me to know where I’d been, where I was, and where I was going. In that sense, I felt much more connected to the places I traveled through. Additionally, although the notifications were incredibly effective at grabbing my attention, they somehow also didn’t come off as overpowering or obnoxious. They were far subtler than all of the cues that are provided by smart phones, and I knew that if I needed some peace, they could be disabled with a few button presses. Finally, using the alerts throughout the trip was an experiment unto itself which provided joy to me in its own right.

The final question is the most interesting: did the proximity alerts on the Fenix actually help with navigation throughout our trip? Without any doubt, I can provide a resounding Yes to this question! It’s worth saying that the real key to successful navigation down the Grand Canyon was the guidebook from RiverMaps. The guidebook was the vault of information that helped us know where to camp, which rapids to scout, and which hikes were worth a stop. It seems obvious, but what the proximity alerts provided was accurate information of our current location on the guidebook maps.

The final question is the most interesting: did the proximity alerts on the Fenix actually help with navigation throughout our trip? Without any doubt, I can provide a resounding Yes to this question! It’s worth saying that the real key to successful navigation down the Grand Canyon was the guidebook from RiverMaps. The guidebook was the vault of information that helped us know where to camp, which rapids to scout, and which hikes were worth a stop. It seems obvious, but what the proximity alerts provided was accurate information of our current location on the guidebook maps.

Within our small group of adventurers, we had a perfect cross section of people to compare navigational techniques. We had someone who’d been down the canyon before who wasn’t using a GPS or a guidebook, and not surprisingly, she rarely knew where we were and therefore depended on the rest of the group for navigation. We had another woman who had done several river trips down the canyon and who also carried a guidebook on her kayak deck, but who was unable to keep track of her place within the guidebook without our assistance. We even had a former Grand Canyon Park Ranger who knew the canyon intimately but who didn’t carry a guidebook or GPS and was also dependent on us for navigation. Finally, our trip leader carried the guidebook on his kayak deck and diligently kept track of our progress using the landmarks that he was so familiar with in the canyon. But ultimately, even he was often far off in his estimates of our location, and it was the two people who had never been down the canyon before (Peter and I) who were able to say with utmost confidence where we were and what was coming up around the corner.

For 280 miles in one of the most isolated and forbidding places in America, not once did I feel lost or uncertain of my navigation and for that reason alone, I think using proximity waypoints on my Fenix GPS is one of the best possible uses of a GPS in the backcountry. It’s unlikely that I will kayak the Grand Canyon again the way I did in February, but I will undoubtedly paddle many new rivers and hike new trails in the years to come and you can be sure that I will be using proximity alerts to help me navigate those adventures.

I encourage you to try using proximity alerts for your own adventures (hiking, biking, kayaking, etc.) and let me know what you think of it in the comments field below!

Back to Grand Canyon 2014 Main Page

Read the previous Grand Canyon 2014 article, Grand Canyon Gear Preparation

[…] to limit the number of electronics gadgets I brought with me down the canyon, but as I described in my Proximity Waypoints article, I made regular use of my Garmin Fenix GPS watch and needed a way to charge it each […]

I am curious about battery life during the trip?

Thanks for all the information. Downloaded your files even though this is my 4th trip.

This page and your other Grand Canyon self support pages are awesome. That is exactly what I am planning— If I would prefer to not have proximity alerts on every campsite, would I have to turn the proximity alerts off individually one by one through each campsite waypoint? Or is there a way I can select all campsites and turn off proximities? Thanks for these articles. Any other help is just icing on the cake.