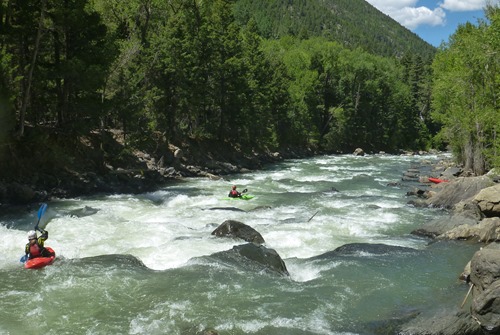

The Upper Animas River is considered by many kayakers to be the most scenic and worthy stretch of whitewater in the state of Colorado. After its beginnings at 9300 feet in the historic mining town of Silverton, the river gains speed as it descends 2800 feet on it course to Durango. The mountain river is icy cold as evidenced by the dramatic, snow-capped San Juan mountains that rise in all directions. The location is also among the most remote in Colorado with no road access for almost 30 miles, but with an anachronistic steam train that now transports tourists instead of silver and gold along the Durango-Silverton Line parallel to the river.

The Upper Animas River is considered by many kayakers to be the most scenic and worthy stretch of whitewater in the state of Colorado. After its beginnings at 9300 feet in the historic mining town of Silverton, the river gains speed as it descends 2800 feet on it course to Durango. The mountain river is icy cold as evidenced by the dramatic, snow-capped San Juan mountains that rise in all directions. The location is also among the most remote in Colorado with no road access for almost 30 miles, but with an anachronistic steam train that now transports tourists instead of silver and gold along the Durango-Silverton Line parallel to the river.

The logistics of a whitewater kayak trip on the Upper Animas River are far from trivial—it’s about 7 hours from Denver, the stretch of whitewater is about 25 miles (a very long day trip or an overnight trip), and the rapids are significant (Class IV to V). These characteristics keep most kayakers away from this river but for those with the right resolve, determination, and connections, the trip definitely offers an unparalleled paddling experience.

Throughout my kayaking career, I heard stories of the famed Upper Animas but always considered it above my ability and beyond my mental reach to make such a trip happen. But after stepping up my paddling the past several years to include Class V- runs, I was graced with an invitation to paddle the Upper Animas from a fellow Colorado Whitewater member also named Patrick. He has organized about half a dozen of these trips and has the entire process dialed-in with a group of experienced paddlers who I have also befriended the past few years.

The trip was scheduled over a Sunday-Monday time period, so I took off a few days from work to allow for travel and some additional paddling on the way to Durango. Early Friday morning, I departed Boulder with Peter in his truck along with our creek boats, play boats, and camping gear. We beelined it west to Glenwood Springs along with Cindy, Stacey, and Dan where we spent a few enjoyable hours in our playboats on the Glenwood Wave. The wave was at a somewhat awkward 8000cfs that resulted in more of thumpy hole than a wave, but the sun was out and we were in our boats so life was good. In between sessions on the water, I got to play with my Pentax SLR and captured a bunch of photos that you can see in this album.

The trip was scheduled over a Sunday-Monday time period, so I took off a few days from work to allow for travel and some additional paddling on the way to Durango. Early Friday morning, I departed Boulder with Peter in his truck along with our creek boats, play boats, and camping gear. We beelined it west to Glenwood Springs along with Cindy, Stacey, and Dan where we spent a few enjoyable hours in our playboats on the Glenwood Wave. The wave was at a somewhat awkward 8000cfs that resulted in more of thumpy hole than a wave, but the sun was out and we were in our boats so life was good. In between sessions on the water, I got to play with my Pentax SLR and captured a bunch of photos that you can see in this album.

By mid-afternoon, we were back on the road to the Crystal River. We stopped at the Crystal Narrows section that was flowing at 1200cfs, and I began to face my own personal fears. Just days prior was the one year anniversary of Jon Boling’s death on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. An Idaho newspaper published a 3-piece article about his death on the Middle Fork that I read, and as I embarked on my journey, it was impossible to shake those thoughts from my mind. I began to question the very idea of paddling whitewater and with only a few days on the water in 2013, I began to doubt my own abilities and motivations. As I viewed the non-stop, Class V flume of the Crystal Narrows, I knew without a doubt that it was not for me. As a group, we decided to move further up river and instead paddle the Class IV stretch of the Crystal River known as Bogan Canyon.

As it turned out, the Bogan Canyon stretch of river from the town of Marble to Bogan Flats campground was a total hoot at 1200cfs. No one in our crew had paddled Bogan before, and as we progressed directly into the low-angle, end-of-day sun, the river features took on a more challenging character. Spray from the large waves and holes became blinding white curtains when coupled with the sun, and the uncertainty of downed trees in the river suddenly made this fun run into a white knuckle experience for me. Six miles and an hour later, we were back at camp with one new stretch of river down and empty stomachs that were soon satiated at Slow Groovin’ BBQ in Marble .

On Saturday, we wound our way up and over McClure Pass, through the agricultural flatlands near Delta, and by mid-day had arrived at the rock sentinels in Ouray that mark the entrance to the San Juan Mountains. The paddling guidebook mentioned two stretches of kayaking in Ouray, and at first we checked out the formidable/unrunnable stretch through the box canyon. Gazing down into the abyss that houses the winter ice climbing park, the actual thought of kayaking the ribbon of water never even entered my mind. Instead, we headed north through town in favor of a quick run on the Quality Quicky stretch of the Uncompaghre River. It was another new river section for everyone in the group, and in 30 minutes, we covered 3 miles of fun, stompy creek water at 450cfs. Just like that, I had shaken off more of my paddling cobwebs and we were back on the road up and over the Million Dollar Highway via Silverton and en route to Durango. That evening, we joined forces with the other members of our Animas group and enjoyed a barbeque at a riverside park in town and began to discuss the logistics of the next day’s start on the Upper Animas River.

The town of Silverton is nestled high in the San Juan mountains with the Upper Animas River snaking through its alpine meadows. As we reached the put-in, I still felt trepidation despite two days of solid warm-up runs. Perhaps hesitancy is a natural reflex when heading into the unknown that is meant to heighten the senses and ensure survival. In any case, as my boat slid into the water to start the Animas trip, I was at once in awe of my immediate surroundings and nervous of what lay ahead on the river.

The Upper Animas begins as a mellow Class 2 float as it slowly winds its way south. Within a mile, the broad valley is left behind along with all sights of the road and is replaced by encroaching hillsides that quicken the pace of the flowing river. As we began our float, I deliberately soaked in the sights of the San Juans and reminded myself to smile and enjoy the whitewater. Class 3 rapids soon joined their Class 2 brethren, and I settled into a rhythm. The water was a medium-low level of around 800cfs (Tacoma gauge) and I was quite content to experience the Upper Animas my first time at a manageable level. As we continued steadily down the river and went around bends, we were treated time and time again to majestic views of the San Juan mountains high above us that contained the year’s last remaining snow pack. I gazed at the alpine scenery, felt relaxed in my boat for the time being, and counted my graces to be fortunate enough to travel through the landscape under my own power in a kayak.

An hour and a half after settling into the water, we reached the first of the major rapids—Garfield (aka 10 Mile) Slide. As we scouted the long cataract, nervousness re-entered my consciousness, but after watching a few boaters eddy-hop their way down, I knew I would be fine and decided to have a little fun myself. I tried to show off for Peter and his camera, and wound up running part of the drop backwards before correcting my boat angle and gliding through the rest. Rather than slowing into a pool like many other rivers, the action continued for another mile of playful Class 3 that left a huge smile across my face as we recollected and ate our lunches under the sun on a boulder next to the river.

An hour and a half after settling into the water, we reached the first of the major rapids—Garfield (aka 10 Mile) Slide. As we scouted the long cataract, nervousness re-entered my consciousness, but after watching a few boaters eddy-hop their way down, I knew I would be fine and decided to have a little fun myself. I tried to show off for Peter and his camera, and wound up running part of the drop backwards before correcting my boat angle and gliding through the rest. Rather than slowing into a pool like many other rivers, the action continued for another mile of playful Class 3 that left a huge smile across my face as we recollected and ate our lunches under the sun on a boulder next to the river.

We continued on for about 2 miles to a sudden constriction that resulted in an uncharacteristic pool of almost unmoving water. When water gets damned up, it typically means that there is a big rapid just beyond. And in this case, it was mostly true. Just over a year ago in May of 2012, the mountainside gave way creating a landslide that completely chocked up the river and covered the railroad tracks. Eventually, the tracks were cleared, water flowed again, and a new rapid was born. The new feature has been referred to colloquially as the new landslide rapid, and there seems to be an effort to name it after Daryle Bogenrief, a popular Durango raft guide who lost his life on the Upper Animas in 2005. For such a major constriction, the rapid boated surprisingly easy probably due to the nearly homogenous nature of the rocks that were deposited in the river bed. Nonetheless, half a mile downstream downstream lay a much more formidable rapid.

No Name is the God Father of all the rapids on the Upper Animas—it is storied and to be respected. We scouted along the right shore, and within a few minutes, I had objectively assessed the moves needed to successfully navigate the many small holes, the big S-turn, the main diagonal 6 foot drop, and a run out filled with several more holes. Any one part of the rapid seemed completely manageable, but I knew that it was all or nothing and that made it a bona fide Class 5 drop. Despite being able to picture my every stroke and subtle body movements through the splashes and big hits, it just didn’t feel right and I knew I had to portage. The combination of difficulty, remoteness, and my recent uneasiness all collaborated in the uncomfortable decision to watch many of my friends run the drop smoothly while I sat idly on the banks. Decisions like that are always difficult and easy to second guess, but I felt more compelled to finish the Upper Animas without incident than I did to complete it in its entirety.

Following No Name Rapid were several miles of continuous Class 3 replete with rocks and eddies that made for a non-stop slalom course. In the wake of my humble portage, I threw myself at everything in my sights and by the time I reached camp 45 minutes later, I had achieved the definitive sensation of flow. I was completely in tune with my kayak, the current, the rocks, and the eddies. All external thoughts were vanquished, and it was just me and the river. I was saddened to stop paddling, and deep satisfaction replaced the fear of days prior and the disappointment of portaging.

About half way through the Upper Animas is a train stop called Needleton that consists of several rustic camps including the backcountry site owned by Mountain Waters Rafting. Among Patrick’s organizational roles, he had arranged for our gear to be deposited by the train at the Needleton stop along with food and beer that were graciously hauled by Dave Eckenrode back to camp. Large, rustic A-frame tents dotted the river side along with an eclectic mix of hand built seats and a horse shoe pit. Set within one of the tents, we prepared a fajita dinner and enjoyed ice-cold beer while telling stories of the day’s adventures before settling down for a much deserved night of sleep.

When the sun rose, I awoke with a confidence that had been lacking the previous days. We lazily prepared and ate breakfast before packing and departing camp mid-morning. Two miles later, we reached the last big rapid in the main section of the Upper Animas—Broken Bridge Rapid. Some folks attempted to scout along the left shore, but after I quickly hopped out of my boat for a peak of what lay ahead, it became clear that the length of the rapid coupled with an ability to boat-scout from numerous eddies made the shore-scout cumbersome and unnecessary. Given the low water level, Broken Bridge was a friendly Class 4 reminiscent of the Roaring Fork’s Slaughterhouse section. The only eventful thing about the rapid was that after two years of faithful service on the water, my Panasonic TS-3 camera stopped working and with that, my trip photos also ceased.

Click here to open the photo album in its own window

Ten miles of Class 2 and 3 water followed, and by mid-afternoon we had reached the Tacoma power station. Tacoma is the traditional finish to the Upper Animas, but when flows and desire are just right, the 3 miles downstream can also be navigated. The Rockwood Box is the climax to the Upper Animas’ crescendo that has been building for over 24 miles. The Box is completely committing with vertical granite walls that contain the river and paddlers within its confines and eliminate the possibility of scouting the Class 4+ rapids. With no means of exit until its completion, paddlers must be absolutely certain that they can tackle the challenges that lie within Rockwood Box before they drift into its entrance.

After four days of paddling, my initial hesitancy had been replaced by well-earned confidence, but still, a respectable nervousness remained as we rounded bend after bend and the walls closed in around us. Among the talk in camp the previous night, Dave Eckenrode advised us on the most formidable rapid—The Guardian. The recommendation was really quite simple—don’t go down the center or left sides of the drop since they lead directly into a huge hole; rather, stay 3 feet from the right wall and throw in all sorts of low braces to avoid getting flipped by weird lateral waves. We approached the horizon line, and one by one, paddlers disappeared down the right side. Like a lemming, I followed in line and quickly found myself skipping down the tight chute adjacent to the rock wall with my boat and body in near perfect balance. Just like that I was through the Guardian and sitting comfortably in an eddy below waiting for the rest of the group to have their shot. Despite several flips, everyone made it through the entrance rapid without drama and we pushed on through the canyon. The water moved quickly and required focus, but it was impossible to not gaze at the surrounding granite walls that enclosed us. More rapids followed in succession—usually largish drops that consisted of big lateral waves and a hole or two to be avoided, but nothing beyond solid Class 4. As each drop was replaced by another, my confidence and spirit soared higher and higher. Without a doubt, the scenery, the whitewater, and the camaraderie that I experienced in Rockwood Box was the culmination and pinnacle of not only the Upper Animas River, but of my entire decade-long paddling career. All too quickly, we reached the ominous sign on river-right that marked the take-out. Travel beyond that sign leads to certain death in the unnavigable, siv-ridden lower box canyon. We all easily exited our boats and expressed our congratulations and thanks to each other for such a perfect run through Rockwood Box and the Upper Animas. I was filled with a feeling of pure and utter ecstasy that wasn’t even dampened by the 700 foot climb out of the Box with a 50+ pound boat on my shoulder in the scorching sun.

The Upper Animas trip had reached its end and by noon the next day, I was exhausted and back in Boulder. Since I had already taken the day off work, I decided to join a crew who was paddling the Lawson-Dumont section of Clear Creek near Idaho Springs. I arrived to find just Steve and Kurt from our Animas trip, and 1100cfs of high-water coursing down the river bed. The Lawson section had been high on my to-do list for years, but I was cautioned that it would be very fast and difficult for my first time due to the high flows. In strong contrast to the fear and hesitancy that cloaked me just days prior, I responded positively to the words of advice and with absolute certainty. I was fully prepared for the challenge and was confident that it would be fun. That run was unlike any I had ever done before; it was fast and furious and big, and yet my consciousness was cool and collected. I moved with purpose and with grace as the water tried to push me to and fro. We never scouted the approaching drops, and despite some drama due to a swim, I remained business-like in my dealings with the river. It felt like I was watching myself paddle from afar. The challenge and my ability were perfectly in balance, and I achieved the hard-fought, but magical sense of flow.

The Upper Animas trip had reached its end and by noon the next day, I was exhausted and back in Boulder. Since I had already taken the day off work, I decided to join a crew who was paddling the Lawson-Dumont section of Clear Creek near Idaho Springs. I arrived to find just Steve and Kurt from our Animas trip, and 1100cfs of high-water coursing down the river bed. The Lawson section had been high on my to-do list for years, but I was cautioned that it would be very fast and difficult for my first time due to the high flows. In strong contrast to the fear and hesitancy that cloaked me just days prior, I responded positively to the words of advice and with absolute certainty. I was fully prepared for the challenge and was confident that it would be fun. That run was unlike any I had ever done before; it was fast and furious and big, and yet my consciousness was cool and collected. I moved with purpose and with grace as the water tried to push me to and fro. We never scouted the approaching drops, and despite some drama due to a swim, I remained business-like in my dealings with the river. It felt like I was watching myself paddle from afar. The challenge and my ability were perfectly in balance, and I achieved the hard-fought, but magical sense of flow.

One of my favorite kayaking expressions is: you only get to make your first descent on a section of river once. I have come to appreciate that expression both literally and metaphorically. For five days in a row on my Upper Animas trip, I descended new sections of river, and the progression I experienced internally was just as unique and special as the rivers and places I explored.

Your insightful last statement, says it all…..the judgment, and wisdom that you gained is priceless. Wonderful pictures and storytelling. You capture the drama of this adventure.