My anticipation for this moment had been building for 6 months, yet I found myself in a panic ridden state as the whine of the rotors increased in pitch directly over my head. The immense bulk of my Big Red parka and the Lilliputian dimensions of the cabin restricted my motions while the multiple legs of the seat belt hid themselves in the darkest nooks and crannies of the collapsible seats. Just minutes prior, we received detailed instructions on how to brace for impact and how to cut the fuel in case of a crash. But without a seat belt, there was no way I would survive an impact with the ground and without a helmet on my head, there was no means of communicating with the pilot who seemed intent on take off in the coming seconds. The rotors continued to whir faster and faster and I felt no closer to readying myself for the first Antarctic helicopter flight of our expedition. I clumsily fumbled as seconds seemed to stretch into minutes and eventually found myself securely attached to the aircraft with helmet fastened as the pilot queried the passengers for confirmation of takeoff readiness. Seconds later, the ground slowly fell away from the helicopter skids in a perception in which the helicopter remained motionless and the world moved around it. Slowly, we changed heading, banked, and pitched towards the sea ice and the sensation of motion set in. And so we were off to our first installation in a rush that was reminiscent of the previous weeks’ progress.

My anticipation for this moment had been building for 6 months, yet I found myself in a panic ridden state as the whine of the rotors increased in pitch directly over my head. The immense bulk of my Big Red parka and the Lilliputian dimensions of the cabin restricted my motions while the multiple legs of the seat belt hid themselves in the darkest nooks and crannies of the collapsible seats. Just minutes prior, we received detailed instructions on how to brace for impact and how to cut the fuel in case of a crash. But without a seat belt, there was no way I would survive an impact with the ground and without a helmet on my head, there was no means of communicating with the pilot who seemed intent on take off in the coming seconds. The rotors continued to whir faster and faster and I felt no closer to readying myself for the first Antarctic helicopter flight of our expedition. I clumsily fumbled as seconds seemed to stretch into minutes and eventually found myself securely attached to the aircraft with helmet fastened as the pilot queried the passengers for confirmation of takeoff readiness. Seconds later, the ground slowly fell away from the helicopter skids in a perception in which the helicopter remained motionless and the world moved around it. Slowly, we changed heading, banked, and pitched towards the sea ice and the sensation of motion set in. And so we were off to our first installation in a rush that was reminiscent of the previous weeks’ progress.

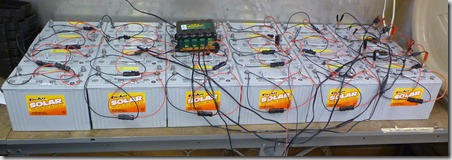

After a fast paced first week in McMurdo, we settled into a work rhythm that involved repeated construction and disassembly of the four ozone stations. We began our assembly practice on the UNAVCO power system which we had previously constructed twice back in Colorado, and therefore felt confident in its selection as the first system for deployment. On its third construction, we chose to deploy the system to the oh-so-far reaches of the Crary Lab parking lot to assist in field testing its components prior to final deployment to Marble Point. The system was outfitted with two 80 watt solar panels, two 5 watt vertical wind turbines, and a dozen sealed lead acid batteries on its aluminum tubing frame. Batteries, oh batteries. Although this research project is aimed at understanding ozone, you could easily be mistaken into believing that its purpose was simply to work with batteries. Among the required job criteria was the most important of all- Must be willing to carry and care for 70 pound batteries. The staggering array of batteries was large enough to power a suburban house, and each of these lead beasts had to be measured, charged, and carried countless times before the systems could even be considered ready for installation in the final sites. While the ozone instruments required careful engineering design and scientific insight, the remainder of the system was an exercise of manual labor which simply could not be escaped but fortunately required an expert in battery carrying and charging from someone just like me.

After a fast paced first week in McMurdo, we settled into a work rhythm that involved repeated construction and disassembly of the four ozone stations. We began our assembly practice on the UNAVCO power system which we had previously constructed twice back in Colorado, and therefore felt confident in its selection as the first system for deployment. On its third construction, we chose to deploy the system to the oh-so-far reaches of the Crary Lab parking lot to assist in field testing its components prior to final deployment to Marble Point. The system was outfitted with two 80 watt solar panels, two 5 watt vertical wind turbines, and a dozen sealed lead acid batteries on its aluminum tubing frame. Batteries, oh batteries. Although this research project is aimed at understanding ozone, you could easily be mistaken into believing that its purpose was simply to work with batteries. Among the required job criteria was the most important of all- Must be willing to carry and care for 70 pound batteries. The staggering array of batteries was large enough to power a suburban house, and each of these lead beasts had to be measured, charged, and carried countless times before the systems could even be considered ready for installation in the final sites. While the ozone instruments required careful engineering design and scientific insight, the remainder of the system was an exercise of manual labor which simply could not be escaped but fortunately required an expert in battery carrying and charging from someone just like me.

After attending to the endless battery charging and the completion of the UNAVCO power system, we progressed towards our first assembly of the Wisconsin power systems which were previously unknown to us. The Wisconsin systems were almost identical clones of the established UNAVCO versions and we quickly discovered that the alternate design proved no more challenging as we assembled three of the units over the course of the next two weeks. Days filled themselves with the construction of the power systems in the parking lot and then progressed to their disassembly into components that could fit within the tight confines of the helicopter cabin.

After attending to the endless battery charging and the completion of the UNAVCO power system, we progressed towards our first assembly of the Wisconsin power systems which were previously unknown to us. The Wisconsin systems were almost identical clones of the established UNAVCO versions and we quickly discovered that the alternate design proved no more challenging as we assembled three of the units over the course of the next two weeks. Days filled themselves with the construction of the power systems in the parking lot and then progressed to their disassembly into components that could fit within the tight confines of the helicopter cabin.

As an additional means of testing the ozone instrument, on Saturday, January 7th, we piled ourselves, our cold weather gear, and a test version of the instrument into a tracked vehicle called a Pisten Bully and headed out onto the ice shelf to deploy it in a remote location free of pollutants called Windless Bight. The Pisten Bully is a passenger carrying version of snow cats that groom ski hills and as such can trudge through any snow conditions but at a painfully slow pace. Two hours of rumbling and rattling over the snow later, we arrived at an instrument site on the ice that is configured to detect nuclear explosions anywhere on the globe, and within 30 minutes, the compact ozone instrument was securely mounted and collecting data. And true to form, the test unit proved its worth as its telemetry revealed an issue to Lars a week later back in the comfort of the Crary Lab. If the issue proved to be systematic, it would be important to understand it before all the systems were released to the wild, so on January 18th we set out on another 4 hour excursion in the Pisten Bully to the remote ice location. Fortune was on our side that day as the issue was determined to be fixable in software, and the day’s initially overcast weather gave way to reveal the towering Mount Erebus and Mount Terror high above us. Not only did we begin to accomplish our technical goals at Windless Bight, but much to my satisfaction, we also began to embark on our adventures to the ice.

As an additional means of testing the ozone instrument, on Saturday, January 7th, we piled ourselves, our cold weather gear, and a test version of the instrument into a tracked vehicle called a Pisten Bully and headed out onto the ice shelf to deploy it in a remote location free of pollutants called Windless Bight. The Pisten Bully is a passenger carrying version of snow cats that groom ski hills and as such can trudge through any snow conditions but at a painfully slow pace. Two hours of rumbling and rattling over the snow later, we arrived at an instrument site on the ice that is configured to detect nuclear explosions anywhere on the globe, and within 30 minutes, the compact ozone instrument was securely mounted and collecting data. And true to form, the test unit proved its worth as its telemetry revealed an issue to Lars a week later back in the comfort of the Crary Lab. If the issue proved to be systematic, it would be important to understand it before all the systems were released to the wild, so on January 18th we set out on another 4 hour excursion in the Pisten Bully to the remote ice location. Fortune was on our side that day as the issue was determined to be fixable in software, and the day’s initially overcast weather gave way to reveal the towering Mount Erebus and Mount Terror high above us. Not only did we begin to accomplish our technical goals at Windless Bight, but much to my satisfaction, we also began to embark on our adventures to the ice.

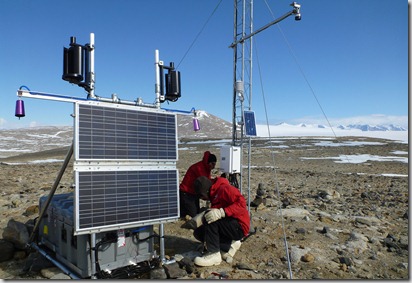

Weeks of travel, hard work, and confined living conditions eventually took a toll on my body as it succumbed to the dreaded McMurdo Crud. During the first days of the cold, I suffered through sniffles and decreasing energy levels but eventually found myself bed ridden on my day off while others frolicked outside in the sunshine. While it pained me to spend my free time sleeping the day away, there was impending reward or punishment depending on how my body responded to the rest, since we were scheduled to fly to Marble Point the following day for our first real field installation. So after a full day of deliberate rest that allowed me to rally for the occasion, I found myself in that panicked state in the helicopter cabin on Monday, January 16 on my way to Marble Point. The cramped cabin was occupied by our team and another party of 3 and much to my chagrin, I was wedged tightly in the center of the craft where the views and photographic possibilities were extremely limited. Nonetheless, the half hour ride proceeded smoothly across the sea ice and then the helicopter pilot revealed the amazing capabilities of the craft as he glided effortlessly over acres of cliché Martian landscape in search of our desired installation site adjacent to the Wisconsin weather station. After a perfect touch down on a tent-site-sized landing spot, we efficiently gathered our personal belongings off to the side and awaited the arrival of a second helicopter that contained the power system equipment. In a scene reminiscent of the opening to TV’s M.A.S.H., we offloaded the equipment from the second copter while its rotor blades continued to spin over our heads. A few minutes later, we had collected all of our gear and the helicopter departed, leaving us alone on the Antarctic continent for the first time in a scene that we had rehearsed and anticipated so many times. After all of that preparation, the time had finally come to execute the plan.

Weeks of travel, hard work, and confined living conditions eventually took a toll on my body as it succumbed to the dreaded McMurdo Crud. During the first days of the cold, I suffered through sniffles and decreasing energy levels but eventually found myself bed ridden on my day off while others frolicked outside in the sunshine. While it pained me to spend my free time sleeping the day away, there was impending reward or punishment depending on how my body responded to the rest, since we were scheduled to fly to Marble Point the following day for our first real field installation. So after a full day of deliberate rest that allowed me to rally for the occasion, I found myself in that panicked state in the helicopter cabin on Monday, January 16 on my way to Marble Point. The cramped cabin was occupied by our team and another party of 3 and much to my chagrin, I was wedged tightly in the center of the craft where the views and photographic possibilities were extremely limited. Nonetheless, the half hour ride proceeded smoothly across the sea ice and then the helicopter pilot revealed the amazing capabilities of the craft as he glided effortlessly over acres of cliché Martian landscape in search of our desired installation site adjacent to the Wisconsin weather station. After a perfect touch down on a tent-site-sized landing spot, we efficiently gathered our personal belongings off to the side and awaited the arrival of a second helicopter that contained the power system equipment. In a scene reminiscent of the opening to TV’s M.A.S.H., we offloaded the equipment from the second copter while its rotor blades continued to spin over our heads. A few minutes later, we had collected all of our gear and the helicopter departed, leaving us alone on the Antarctic continent for the first time in a scene that we had rehearsed and anticipated so many times. After all of that preparation, the time had finally come to execute the plan.

Methodically, we set about building the frame and then found ourselves executing the one part of the plan we had not practiced already. On a continent known for extreme weather, the power system bears a striking resemblance to a ship with sail lofted, and the last thing we wanted was for the ozone system to be tumbling across the ice sheet like a sad, green port-a-potty on the side of I-80 in Wyoming. Two of the frame corners were near bedrock, so we drilled 1/2” diameter holes and inserted purpose-built rock bolts that provide ideal anchor points. The other two corners lacked bedrock, so we laboriously hammered 1-inch steel spikes a foot and a half into the ground and then attached the 4 corners of the frame to the anchors with chain. With that taken care of, we returned to our usual routine by adding solar panels, wind turbines, and the Hardigg cases to the frame. Then of course, we lugged 12 batteries and placed them in the Hardigg cases and began the careful procedure of electrically testing and connecting each component of the power system. In order to communicate the instrument data with the outside world, Lars connected the ozone station to an existing radio transmitter in the Wisconsin weather station and the instrument was finally powered on. Minutes later, it sprung to life with its familiar pump buzzing aloud just as it had done so many times in the lab before. The installation was complete after 5 hours with an hour to spare before the helicopter returned, so we casually explored the immediate area near the station where I was able to capture the panorama below.

The helicopter arrived on schedule, touched down in the same, miniscule landing zone, and we boarded with no more fan fare than hailing a New York taxi as the rotors whipped around over our heads. I was pleasantly surprised to find a more intuitive seat belt in this helicopter and was quickly fastened with none of the grief I experienced on the previous take off. The aircraft yawed and occasionally bucked in the wind as we cruised 600 feet above the sea ice, and my GPS confirmed the blustery conditions when I discovered that we were proceeding 30 mph slower than the 130 mph speed of the first leg. For the first time, I was able to enjoy the helicopter ride over the relatively featureless sea ice and my gaze out the window eventually discovered long, straight tracks that would eventually lead to seals near holes in the ice. Further inspection of the ground showed smaller tracks that I speculated were from penguins and with a few minutes remaining in the flight, I spotted 3 tiny penguins waddling their way along the ice. After a day spent in 16 mph, cool wind, I was ready to return home and the rapidly approaching view of McMurdo comforted me until the helicopter wildly swung to the left and to the right as if gripped by the wind itself. Fear began to set in, but I reminded myself that I was in the trusted hands of an experienced, professional pilot. No sooner had the turbulence started than he had the craft back under control for a safe landing. Half an hour later, we were back in the lab and Lars happily reported the first science data from the Marble Point ozone station!

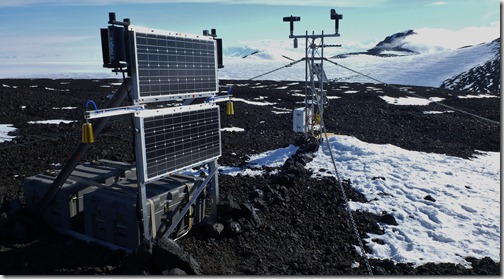

Even with our first field installation under our belt, we weren’t resting on our laurels this past week as we disassembled the first Wisconsin frame for scheduled transport to the Minna Bluff site on Friday. But as often happens with flight schedules, Thursday’s foggy morning backed up flights and bumped our trip until Saturday, January 21. Only five days after our first install, I awoke feeling that I had finally recovered from the McMurdo Crud and readied myself for the day with a hearty, diner style breakfast consisting of sunnyside eggs, hashbrowns, and toast. And as we waited at the helicopter passenger terminal, I prepped myself by emptying Big Red of superfluous items that would interfere with the seat belt, then donned my helmet ahead of time, and only half jokingly went through the motions of putting on the 4 point seat belt. When the time came to board the chopper, I was ready and we effortlessly lifted off and floated across the dead-still sky towards our destination. The distant location of Minna Bluff necessitated a gorgeous flight path that toured us between White and Black islands and past Mount Discovery. Once again, the breathtaking views were difficult to capture on my camera from my interior seating location, but the experience of flight in such a majestic location was not lessened at all. The search for the actual weather station locations is a game that both pilots and passengers seem to truly enjoy as they buzz the ground and arc the machine in tight circles before finally lowering the skids softly to the rocks below.

Even with our first field installation under our belt, we weren’t resting on our laurels this past week as we disassembled the first Wisconsin frame for scheduled transport to the Minna Bluff site on Friday. But as often happens with flight schedules, Thursday’s foggy morning backed up flights and bumped our trip until Saturday, January 21. Only five days after our first install, I awoke feeling that I had finally recovered from the McMurdo Crud and readied myself for the day with a hearty, diner style breakfast consisting of sunnyside eggs, hashbrowns, and toast. And as we waited at the helicopter passenger terminal, I prepped myself by emptying Big Red of superfluous items that would interfere with the seat belt, then donned my helmet ahead of time, and only half jokingly went through the motions of putting on the 4 point seat belt. When the time came to board the chopper, I was ready and we effortlessly lifted off and floated across the dead-still sky towards our destination. The distant location of Minna Bluff necessitated a gorgeous flight path that toured us between White and Black islands and past Mount Discovery. Once again, the breathtaking views were difficult to capture on my camera from my interior seating location, but the experience of flight in such a majestic location was not lessened at all. The search for the actual weather station locations is a game that both pilots and passengers seem to truly enjoy as they buzz the ground and arc the machine in tight circles before finally lowering the skids softly to the rocks below.

As its name implies, Minna Bluff sits high above the sea ice on a coastline promontory akin to that of the British Isles that leaves it particularly susceptible to high winds that arrive unimpeded for thousands of miles along the continental ice. So whenever we discussed Minna Bluff, conversation turned to the gale force winds that we expected would complicate the installation effort. You can imagine our collective surprise when we disembarked the helicopter to find absolutely still air as reflected by the motionless anemometers on the weather station. Without a complaint, we quickly assembled the frame in the warm sunshine, and I even stripped down to a t-shirt during the aerobic spike-driving task. Our understanding of the power systems and each other became apparent as we efficiently divided tasks and made short work of the assembly. After 2 hours, the system was completely assembled mechanically, so we took a brief walk to the bluff’s edge where we enjoyed our lunch and views of endless white that eventually lead to the South Pole. Two hours later, the entire system was up and running and the wind had still not increased to more than a slight breeze. The fortunate conditions and early completion afforded us an opportunity to explore a little farther to another ridge point half a mile away where we took in the views and I shot the panorama below.

As its name implies, Minna Bluff sits high above the sea ice on a coastline promontory akin to that of the British Isles that leaves it particularly susceptible to high winds that arrive unimpeded for thousands of miles along the continental ice. So whenever we discussed Minna Bluff, conversation turned to the gale force winds that we expected would complicate the installation effort. You can imagine our collective surprise when we disembarked the helicopter to find absolutely still air as reflected by the motionless anemometers on the weather station. Without a complaint, we quickly assembled the frame in the warm sunshine, and I even stripped down to a t-shirt during the aerobic spike-driving task. Our understanding of the power systems and each other became apparent as we efficiently divided tasks and made short work of the assembly. After 2 hours, the system was completely assembled mechanically, so we took a brief walk to the bluff’s edge where we enjoyed our lunch and views of endless white that eventually lead to the South Pole. Two hours later, the entire system was up and running and the wind had still not increased to more than a slight breeze. The fortunate conditions and early completion afforded us an opportunity to explore a little farther to another ridge point half a mile away where we took in the views and I shot the panorama below.

The efficient helicopter schedulers decided that our return flight could be combined with that of two more scientists up the coast, so after lift off, the helicopter followed an entirely new route along the termini of the famous Dry Valleys. With an empty helicopter, I was finally able to select a window seat and wisely chose the left side that provided views of my namesake Brown Peninsula and amazing glacial melt pools below. The other two passengers had spent the day surveying an area called Cape Chocolate, and the pea sized gravel bed provided no challenge for the pilot who easily set the craft down in the exact skid marks of his previous landing. In the air again and on our way back to McMurdo, I was amazed by the artistic, fractal patterns on the sea ice and happily took advantage of my excellent vantage point with nonstop shutter clicking of my camera that you can see in the photo slide show below or in a new window.

The warm, still air of the late day provided an effortless landing in McMurdo and minutes later in a tradition that will hopefully continue, Lars was able to report that he received science data from the Minna Bluff station and all was well! With our stay in Antarctica at exactly the half way point, it is encouraging to know that we have successfully completed half of the ozone station installations. We are certainly breathing a little easier, but there is more adventure so stay tuned…